First, though, I want to do a brief review of the book, because it's my party and I'll review if I want to. Review if I want to.

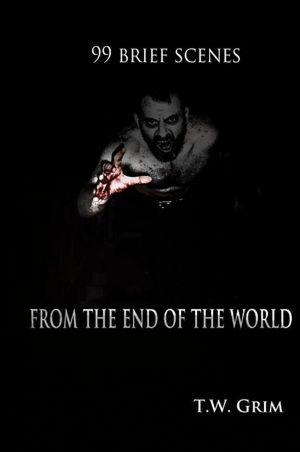

99 Brief Scenes From the End of the World (henceforth 99S) is,

and believe me when I say that I don’t use this term lightly or regularly,

absolutely brilliant. It combines a technique which I've never seen before,

writing 99 stories each several pages in length, with a nearly breathless but

nonetheless well-paced tone. I know I’m

supposed to be in superlative rehab, but I'm jumping off the wagon with both feet because it really is the best thriller I’ve

ever read and in my top 5 books written within my

lifetime. It is also very possibly the most blatant and uncompromising look at

the beauty which lies in ignoring the reader.

Read it, and if you don’t love it quit reading and take up

another hobby because you are clearly just plain not fucking cut out for it.

As for the cultural context, the Not Review portion of this

post, 99S was originally written as a serial on Reddit, a site which is

something like a sequel to that far more famous, or perhaps infamous, hive of

scum and villainy, fiction and falsehood from the olden days of the web. What

that means, for Reddit that is, is that despite its toothless debility it is still in many ways a microcosm of internet culture, a mirror of

the inherent nature of a people which hide at the bedrock center of hundreds of

web communities, providing us with everything from lolcats and trollception to unbounded intellectual inquiry and sociopolitical activism.

99S embodies that same mindset: Digressive, irreverent,

almost combatively uninterested in the comfort of anyone, anywhere; in short, all

that the web is at its best and its worst, with nothing in between. It is a

book which could not exist without untold millions of 1’s and 0’s and the

culture they spawned. The beauty in this is that, unless I miss my guess, the occurrence is entirely unintentional. The book isn’t about the internet, doesn’t say a single word directly about

internet culture; it was simply birthed by a creator possessed

of, or perhaps possessed by, a cultural phenomenon beyond his control.

As writers we are in no way immune to the influences of

culture. Those of us whose egotism is exceeded only by our single-minded

dedication to a goal very nearly unattainable often like to pretend that we

exist in a world unto ourselves, somewhere between a fantasy and a vacuum, but at the risk of disabusing some pleasant notions, no man is island. I would go so far as

to say that we who fancy ourselves artists are more so mirrors of the time and place in which we live,

inadvertently exposing our cultural heritage for the viewing public in a way

which is inextricable not just from the self but also from the collective. From

what some might call the collective unconscious, the zeit- or volksgeist, or if they're dumb and whining at me (as is the wont of so many), the esprit d'corps.

The question, then, is how much is a work truly ours, as writers? Does the fact that we are often

channeling some unseen force, drawing our story not entirely from ourselves but

from the world we live in mean that in some way the work is the property of that collective unconscious? This is not a

rhetorical question.

As an extension of all this, we must face the topic which has occupied my mind for what would be fairly described as an embarrassing amount of time if I was capable of embarrassment; I am consumed by curiosity as to what the literary analysts will (or would...) find in

my work, what voices enter unbidden...

So, I’ll issue this challenge, through not a spirit of

generosity I’ve never possessed but rather in pursuit of what only you may give

me, my dear readers:

If you fancy yourself a literary sort, the sort of person

who finds things the author cannot, email me and I’ll have a PDF of

anything published in your hands in hours, God willing, with the sincere

hope that you will return to me a work of sublime insight somewhere between 1

sentence and a graduate thesis.

In the meantime, abandon your thoughts of my work, and bury

yourself in Mr. Grim’s. It is, in a word, unapologetic, reveling carelessly in a

quagmire of the sort of guiltless imperfection which stands in stark contrast

to self-conscious literary vanity, a

paragon of the nearly imperceptible.

I didn’t care for the ending, but you know what? Fuck my

ending. And fuck yours, too. Genius answers to no one, or in failing to abandons

itself to the mob.